Understanding ALS

Understanding ALS

ALS Pathophysiology:

A Degenerative CNS Disease

ALS is a devastating neurodegenerative disease primarily characterized by the degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons.

ALS begins as a focal process then spreads throughout the motor system, causing neuron loss – from the cortex, to the anterior horn of the spinal cord.

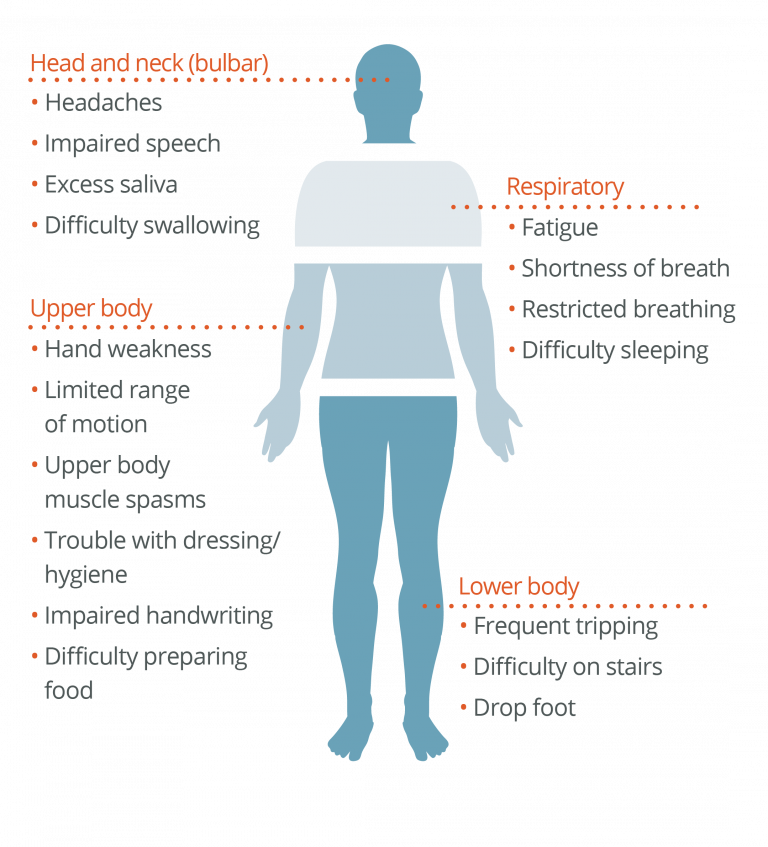

The process of neurodegeneration may vary from patient to patient. However, symptom progression in different parts of the body can occur in an organized manner.

The onset of ALS may be so subtle that the symptoms are overlooked. By the time the first symptoms of ALS are noticeable, the underlying pathophysiology has already resulted in neuronal damage.

Late Effects of Neurodegeneration1,2

Motor neurodegeneration eventually causes weakness of all voluntary muscles and progressive paralysis. ALS gradually spreads to muscles involved in speaking, swallowing, and breathing. The leading cause of death in ALS is respiratory failure.

of ALS

ALS Causes: Theorized Mechanisms

of

Neurodegeneration1,2

Research suggests many factors may contribute to motor neuron cell deterioration, including:

- Oxidative stress

- Defective glutamate metabolism

- Mitochondrial dysfunction

- Genetic variations

- Apoptosis

- Altered protein and neurofilament metabolism

- Autoimmune dysfunction

- Inflammatory responses

- Oxidative stress

- Defective glutamate metabolism

- Mitochondrial dysfunction

- Genetic variations

- Apoptosis

- Altered protein and neurofilament metabolism

- Autoimmune dysfunction

- Inflammatory responses

Diagnosis in ALS

Signs of Differentiating Diagnosis in ALS

Differentiating symptoms may help rule out similar diseases and expedite time to diagnosis.2,3

These include:

- Painless progressive weakness

- Changes in speech and swallowing

- Atrophy

- Weakness spreading from one myotome to another

- Trouble rolling over in bed

- Hand clenching that cannot be voluntarily released

- Lack of bowel or bladder involvement in a spinal diagnosis3

Airlie House Criteria4

Clinically definite ALS has been defined by clinical or electrophysiological evidence, such as:

|

Clinically Definite ALS |

Clinically Probable ALS |

Probable ALS–Laboratory Supported |

Clinically Possible ALS |

|

Defined by clinical or electrophysiological evidence, such as: |

Defined by clinical or electrophysiological evidence of lower motor neuron symptoms and upper motor neuron symptoms in at least 2 regions with some upper motor neuron signs rostral to (or above) the lower motor neuron signs. |

Exists when clinical signs of upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron dysfunction are found in only 1 region, but electrophysiological signs of lower motor neuron are observed in at least 2 regions. |

Defined by clinical or electrophysiological evidence, as follows: |

Function

The Importance of Maintaining Function

Moreover, a decline in functional ability is a valuable indicator of disease progression.1,2